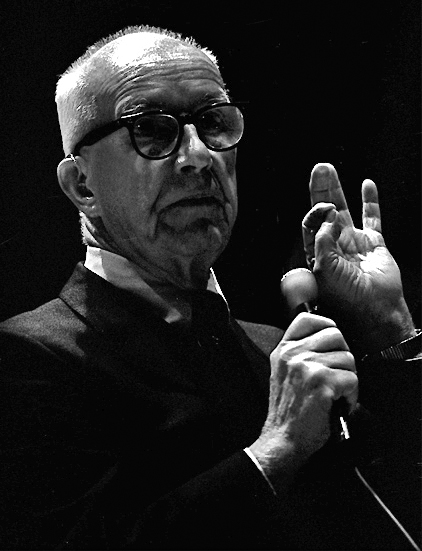

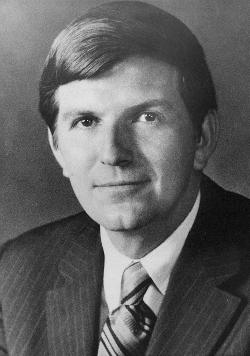

Yuri Shafranik,

co-chair of the Russian delegation

to the Dartmouth Conference

Yuri Shafranik, a strong supporter of public diplomacy, has been deeply involved with Dartmouth for 20 years, initially as a delegate himself and now the Conference’s co-chair. Each delegate, in his or her way, has contributed to maintaining dialogue for peace by improving relations between the US and the former Soviet Union, now Russia - and all essentially on the q.t.

Yuri Shafranik provides an illuminating foreword to Philip D. Stewart’s new 283-page volume ‘Breaking Barriers in United States-Russia Relations: The Power and Promise of Citizen Diplomacy’ available in Kindle and paperback on Amazon by the Kettering Foundation. He is, of course, well placed and qualified to explore and recount the modern evolution of Dartmouth, which he does with such aptitude for the subject in the book. It offers clear insights as to what went on over the six decades, personal anecdotes on his 20 years in annual attendance and engaging recollections of the time when he first connected with his US counterparts way back in 1992.

This very respected and inspirational co-chair of the Dartmouth conference, Mr Shafranik recalls how he was one of the initiators and, as he describes it, ‘engines’ in the Gore-Chernomydrin Commission in 1993. It was initiated by the then respective presidents Bill Clinton and Boris Yeltsin at the Vancouver summit in April of that year. Yuri Shafranik was a leading light in the subsequent design and passing of the law on US-Russian production sharing, which in turn led to mutually beneficial global energy projects. Those at Sakhalin-1 and Sakhalin-2 oil and gas fields in Siberia, centred on a remote Pacific island corner close to Japan, are prime examples.

The end of the Cold War

It was an American political journalist called Norman Cousins who was the driving force behind the Dartmouth Conference’s inception. Cousins had been on the newly-formed National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE). Speaking at the council of the Soviet Peace Committee in 1959, when the Cold War was basically in its throes, he set in motion a proposal to the effect that the US and Soviet administration should meet informally and somewhat covertly each year for discussions in order to broaden contacts on each side and to explore any existing misgivings between them. President Eisenhower gave his blessing to the initiative later that year, and Cousins began his potential participants’ hitlist of prominent citizens of both superpowers.

The American delegation Cousins organised with Professor Philip Mosely of Columbia State University, while it became the remit of the then Soviet Peace Committee to get together the Russian contingent. Therefore the very first Dartmouth Conference sat around the table in the US in October 1960 at Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire. Hence its name. It created the blueprint for the conferences that followed. All tricky issues relevant at the time in East-West relations were aired, and if not completely resolved, certainly the more troublesome aspects were ameliorated. The assembly was kept off the record, and indeed that continued for the 60 years that followed.

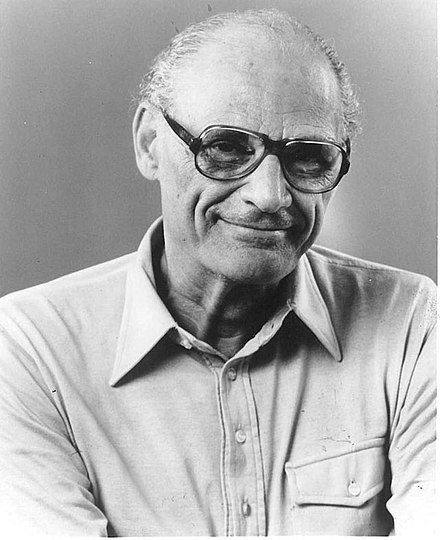

There are certain factors that made Dartmouth stand out over other initiatives to improve Soviet and American relations. For one, those taking part came from a host of different backgrounds and professions. The American contingent at the first Conference included the famous Broadway choreographer Agnes DeMille; Walter Rostow, then an aide to President John F. Kennedy; Grenville Clark, a renowned lawyer; and Senator William Benton of Connecticut. The Soviet delegation was led by one of her prominent playwrights, Oleksandr Korniychuk, and included a chemist, composer, and historian. Later conferences included Members of Congress, top scholars, industrialists, former diplomats, the famous American playwright Arthur Miller - and the award-winning African-American contralto singer and human rights activist Marian Anderson in 2008.

Dartmouth, therefore, became an unobtrusive yet extremely effective tool for dialogue between the Soviets, later the Russian Federation, and the United States of America. For talks on political and economic matters to arms control and indeed the standing of the two countries in the entire world.

Fall of the Berlin Wall

It was in 1970 that the Kettering Foundation took on the main responsibility for manning the American contingent at Dartmouth. In the East, it was Soviet Peace Committee but adjoined to an organisation known as the Institute for US and Canadian Studies (ISKRAN). This arrangement lasted until 1991 - which is recognised as the end marker of the Cold War. Why 1991? Well, it was the year the Soviets withdrew from occupied Afghanistan, the Wall which had been erected in 1961 dividing East and West Germany came tumbling down, and from two years previous, a spate of mini revolutions had bubbled up along the Soviet Bloc states of eastern Europe.

At the start of the 21st century, the Kettering Foundation felt that the time was right for a fresh approach to Russian-American dialogue - and the beginnings of a ‘New Dartmouth’ was being created. Building on the work of the many previous engagements, it’s long history on public deliberation in the US which had been valued and utilised by the country’s National Issues Forums, Kettering set up three groups met to address certain new issues in the relationship between the two superpowers. The dialogue on these issues then filtered down to 25 groups across the country designed to discuss East-West relationships in greater detail. This signified greater citizen involvement at grassroots level.

While this was happening Stateside, two Russian organisations, the Russian Centre for Citizenship Education and the Foundation for the Development of Civic Culture, came into being, and they, in turn, passed down debate to 70 similar forums throughout the Federation. It was like a mirror image of what was going on with their American citizen counterparts.

The new Dartmouth

What came out of these expanded contributions was the formation of agendas for the new Dartmouth - these sessions taking place between 2003 and 2008. These findings were open to greater public accessibility. The hush-hush Dartmouth began to fade away, and the content of the great debate could be read and researched in libraries right across Russian and throughout the National Issues Forums network. The bigger policy issues, of course, remained in the domain of the re-focused Task Force on Regional Conflicts. Yuri Shafranik remains co-chair of the new Dartmouth Conference and is as publicly active today in securing Russia’s best interests in East-West relations as he ever was.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)